It was the 1960s. Times were changing. Social norms were shifting. Popular culture was adrift in questions of ‘why’ and ‘how.’ The Vietnam War was raging, the civil rights movement was underway and college students throughout the nation were realizing a deep longing to connect fields of learning to one another. Science, math, history, literature, music, faith … how did it all connect? Or did it connect at all?

From this swirling of questions and curiosity came a new idea. An idea to remake the curriculum at OBU to ensure a diverse and broad knowledge base, allowing students to connect the dots between fields of knowledge, forever shaping their worldview. An idea that would lead to the singularly definable academic experience for all Bison … western civ.

The Unified Studies Curriculum of 1970

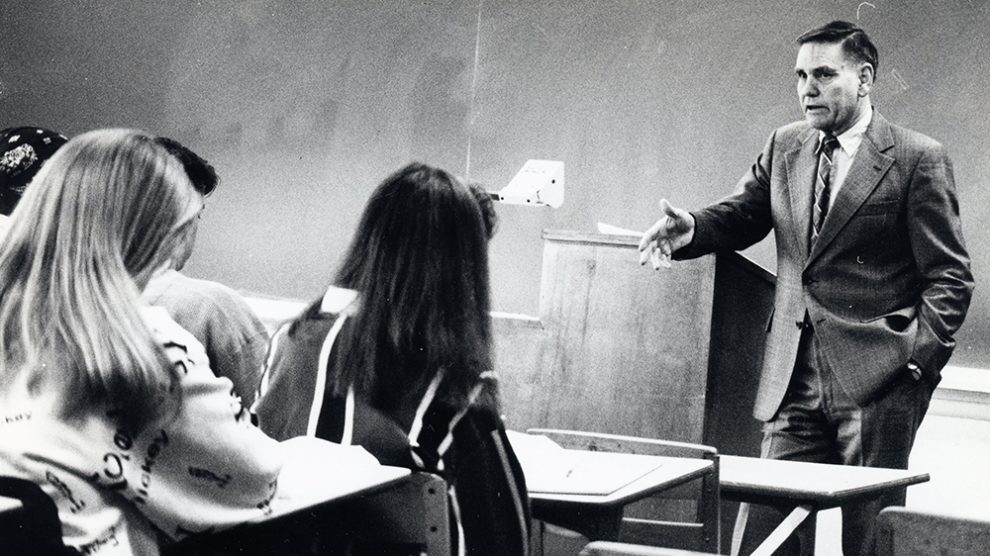

Dr. William (Bill) Mitchell, professor emeritus of English (1958-1997), sat down with OBU Magazine to discuss the origins of the curriculum change at OBU and the commensurate birth of the western civilization courses. His comments are drawn both from that interview, as well as a 2003 video produced by the University on the development of the unified studies curriculum of 1970.

“The world was changing and education was changing,” Mitchell said. “We didn’t want to abandon what we had done so well, but I think there was a little bit of fear in the hearts of many people that unless we came around to the times a little bit, we might very well be left as a dinosaur.”

During the spring of 1966, the University’s academic committee approved an initiative to study the curriculum. In the fall of 1966, under the direction of new OBU President Dr. Grady C. Cothen, the faculty began to work on the development of a new unified studies program.

“Dr. Cothen’s continued focus on the purpose of the University required us to look at the entire product of the student that was coming out of the University,” Mitchell said. “What should they be able to do? What should they know? What kind of person are we trying to develop through this process?”

Students were the driving force behind the entire process of the curriculum revision.

“The genesis of the unified studies idea was with the students,” Mitchell said. “Students were alert and very interested in what was happening [in the world]. They were trying to make sense of it all. The problem was trying to reconcile what they had come to believe about their faith and what they were learning.”

Susan (Baker) Wooten, ’74, vice provost and professor of art at Anderson University in South Carolina, was a freshman during the first year of the new curriculum’s implementation.

“We had no concept of how forward-thinking the OBU faculty had been nor how much work had been expended to develop the unified studies general education program,” she said. “We were the recipients of that great effort, and it was an intellectual gift. It was very progressive for the time, and the habits of mind it cultivated in me have persisted to this day.”

The Birth of “Civ”

Coinciding with the movement toward the unified studies curriculum was another transition already in progress to integrate history and literature courses into what would become known as western civ.

Mitchell and Dr. Jim Farthing taught western civilization pilot courses in the fall of 1969 and spring of 1970 in Shawnee Hall Room 301 with a class of 30 students.

“It was a very exciting and a very strenuous experience,” Mitchell said. “We did what seemed to be the next thing to do, whether it was history or literature, and of course we had to reach into economics, philosophy and religion to explain what was happening in the literature. So it began to be more than a history and literature course, it was sort of a history of thought and a history of practice.”

Shawnee Hall was being remodeled at the time, so they took that opportunity to create U-shaped classrooms to encourage discussion.

Following the pilot course, and as the new curriculum was preparing to launch in full, Mitchell and Farthing shared their experience with the other faculty members. They gathered the English and history faculty and went through the year’s work, duplicating their notes for the other faculty members.

The Legacy of Civ

Dr. Debbie Bosch, dean of the James E. Hurley College of Science and Mathematics, was a student in the first unified studies western civilization classes during the 1970-71 academic year.

“Going into the experience, I would have told you that I hated history, but I soon realized that what I hated was the way I had been taught history up to that point,” she said. “Having the experience of reading the literature of the period of history we were studying, presented by a team of professors challenging us with ‘the BIG questions of life,’ was THE watershed experience of my college experience. It changed my life. It changed the way I thought, the way I wrote and the way I expressed myself. It changed my whole worldview.”

Wooten noted how western civ was a unifying force on campus for the entire sophomore class as all of them were reading and discussing the same text.

“We became acquainted with many of the best minds in the history of western civilization, and we were introduced to a dialogue where faculty from different disciplines and perspectives guided the conversation,” Wooten said. “Even the design of the U-shaped tiered classrooms in Shawnee Hall supported the spirit of discourse in the classes. Sixty people could be fully engaged and see one another’s faces as the discussion developed.”

Lasting Effects

Mitchell credits the western civ course and the new curriculum with making a long-term impact on campus.

“Many times I would get a call at home that students were talking through something and wanted me to talk with them,” he said. “That didn’t happen before. I certainly grew by leaps and bounds from the time I started teaching civ.”

Wooten credits her civ experience with changing her worldview entirely.

“The foundation created by exploring history and ideas, religion and culture, the appreciation of art and science, the capacity to question and understand, this combination of educational experiences significantly framed how I viewed myself and world events over the following decades,” she said.

For Mitchell, the integration of faith with all areas of knowledge has never been so apparent as it is in the thousands of students who enter a U-shaped classroom in Shawnee Hall as sophomores, but leave as world-changers.